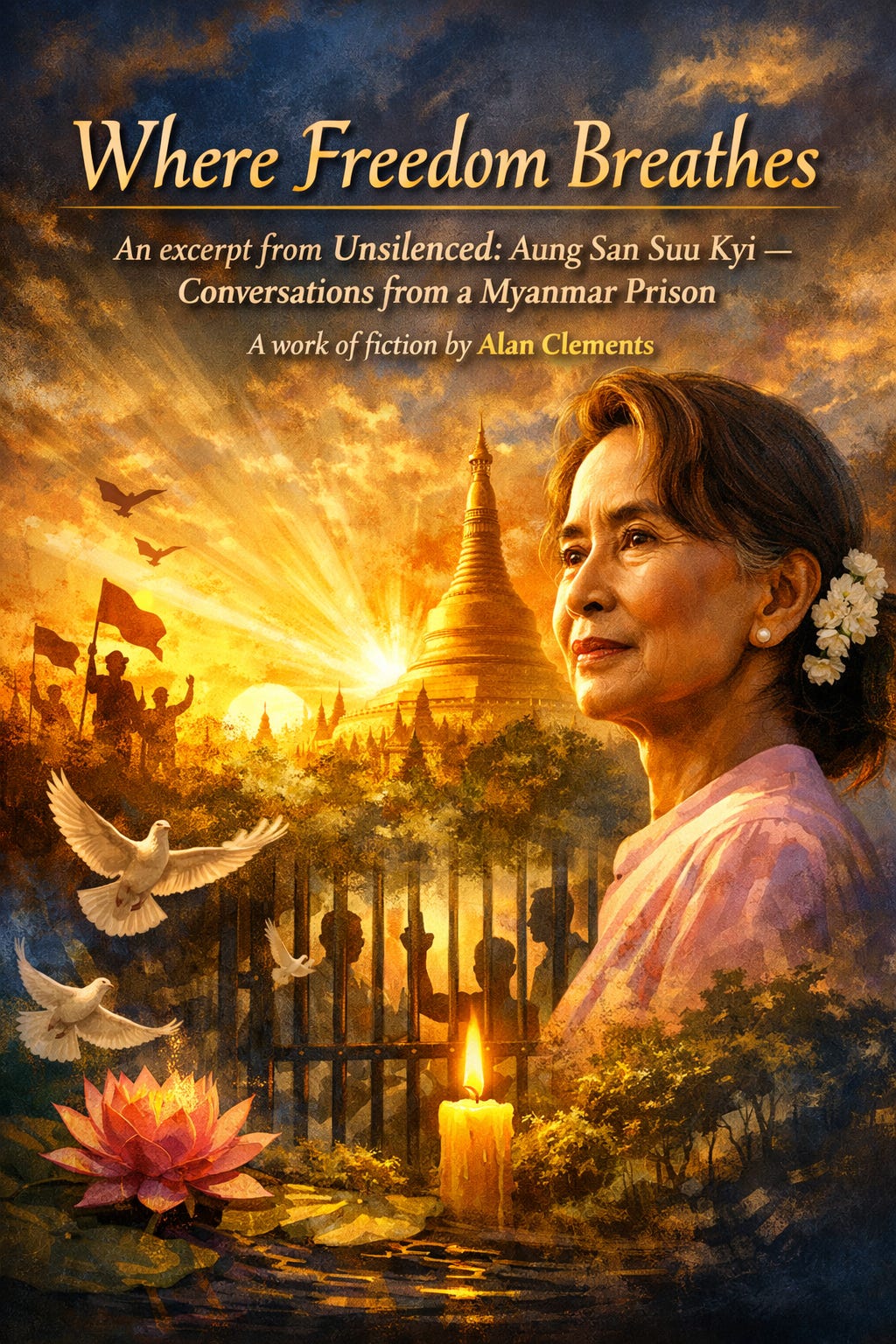

Where Freedom Breathes

An excerpt from Unsilenced: Aung San Suu Kyi — Conversations from a Myanmar Prison A work of fiction by Alan Clements World Dharma Publications

What you are about to read is a fictional dialogue—between myself and Daw Aung San Suu Kyi—from my recent book, the second in a trilogy. These dialogues are fictional only in the narrowest sense. This excerpt is drawn from many sources across time: from earlier books I have written or co-authored, including The Voice of Hope, which Daw Suu and I created together in 1995–1996; from conversations we shared; from dialogues with the late Venerable Sayadaw U Pandita, the Buddhist meditation teacher we both studied with; from her talks, writings, and published articles; and from deep, sustained research into the consciousness of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi herself—her relationship to Dhamma, revolution, freedom, her father, nonviolence, and reconciliation.

It also arises from years of collaborative investigation and witness alongside trusted friends, mentors, and colleagues working closely with senior members of the National League for Democracy, committed to preserving primary truth against distortion. All of it arises from more than forty years of work, witness, and direct involvement in Burma’s struggle for freedom.

I share this excerpt because it touches, in an essential way, the heart of my love for Daw Suu, for the people of Burma, and for the immeasurable gift I received from the culture itself. That gift was formed during the brief yet formative years I spent as a bhikkhu (Buddhist monk) at the Mahasi Sasana Yeiktha in Rangoon, practicing Satipaṭṭhāna insight (vipassana) meditation under my preceptor, the late Venerable Mahasi Sayadaw, and later under his successor, the late Venerable Sayadaw U Pandita. Those years shaped not only my understanding of Buddhism, but my understanding of conscience, dignity, and moral courage.

This work also carries the long and intimate association I shared with Daw Suu herself, and with many of her mentors and closest colleagues—U Tin Oo, U Win Tin, U Kyi Maung, U Win Htein—as well as with countless women and men of the National League for Democracy and the wider movement: students and elders, villagers and prisoners, whose lives illuminated what I consider one of the greatest revolutions I have ever known. As Daw Suu and her colleagues called it, the Revolution of the Spirit.

That work was also made possible through the tireless contribution of my colleague and co-author Fergus Harlow, whose commitment to the people of Burma helped bring the voices and lived words of former political prisoners into the world—most fully through our four-volume series Burma’s Voices of Freedom (2020), a body of testimony shaped by decades of listening, care, and moral fidelity.

I have often said that while Daw Suu is a practicing Buddhist, she is also, in an essential sense, trans-Buddhist. She rooted her understanding of freedom not only in Dhamma, but in the moral clarity of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights—that all beings are born equal in dignity and rights. Conscience and dignity, as she lived them, exist both within and beyond philosophy, psychology, meditation, Buddhism, Islam, Judaism, Hinduism, Christianity—outside religion, yet intimate to all of it. That quality was something I came to love deeply about Burma, and about Daw Suu herself.

In sharing this excerpt, my hope is simple: that it may offer some small but meaningful support to the beloved people of Myanmar as they struggle—daily and courageously—for what many elsewhere take for granted: the oxygen of freedom, democracy, mutuality, and peaceful coexistence. That same hope guided more recent work, including Aung San Suu Kyi from Prison – and a Letter to a Dictator, co-written with Fergus Harlow in response to the February 2021 military coup—an effort to distill lived history, primary sources, and Daw Suu’s own words (2010–2021) into a clear public record resisting the charge of her so-called “silence.” The work was later referred to an international court in Argentina as evidentiary material and offers a concise analysis of Myanmar’s democratic movement, the distortions of international narrative, and the lived experience of its people—serving as a direct rebuttal to accusations of “complicity in genocide.”

I have often spoken with Fergus about what it would take for the generals—especially Min Aung Hlaing—and for the Tatmadaw itself to awaken to the deeper qualities of Dhamma: dāna, sīla, bhāvanā; generosity, moral discipline, and wisdom; mindful intelligence; hiri and ottappa—moral shame and moral conscience.

In other words, what would it take to simply do the right thing—for and by the people of Myanmar, all people, all ethnicities—and not merely for themselves? What would it take for Min Aung Hlaing to go on national television and say:

“I have realized that I have been acting wrongly. I have made a grave error. I am immediately releasing all political prisoners. They are not terrorists. They are freedom fighters challenging my ignorance. They are a gift to our country. Let us lay down our weapons. I will ask my soldiers to cease fire and return to their bases, barracks, and home villages. The war is over. It is time to heal. Let us openly discuss our way forward.”

Idealistic as that may sound, we are watching people across the world—from Iran to Gaza to Myanmar to America and the UK—cry out for freedom and an end to violence. War is dead, in my view. What we require now is a revolution of imagination, a restoration of beauty, and a return to the sacred. The world has had enough—enough oppression, enough mass murder. The era of normalized atrocity is an assault on the conscience of humankind. The genocide of nonviolence, love, and peace must end.

This is why the third book in the trilogy is titled Politics of the Heart: Nonviolence in an Age of Atrocity. It grew directly out of these dialogues—these attempts to enter the lived reality of nonviolence, reconciliation, and peaceful coexistence. How do we collectively put down the fist, the weapon, the drone, the missile, the hate? How do we restrain the reflex to retaliate, and instead come to the middle—and speak?

Alongside Unsilenced, the trilogy includes Conversation with a Dictator: A Challenge to the Authoritarian Assault, a fictional dialogue with Min Aung Hlaing—fictional only because I did not enter Naypyidaw Prison to speak with Daw Suu or the generals. The truths themselves are not fictional. They are lived, witnessed, and embedded, offered here in my own imperfect attempt to pass on what I have received.

Together with Fergus Harlow, director of the Use Your Freedom campaign, I want to say this plainly: all proceeds from this trilogy support efforts to raise awareness and to call on people everywhere to use their voice—and use their freedom—to demand the release of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and the more than 22,000 political prisoners held throughout Myanmar.

Now is the time.

From my heart to yours, thank you for reading—and for sharing this excerpt. Should you wish to go further, Conversation with a Dictator, Unsilenced, and Politics of the Heart together form this offering—created in solidarity with the people of Myanmar, and with all those, everywhere, who still dare to breathe the oxygen of freedom.

An excerpt from Unsilenced: Aung San Suu Kyi — Conversations from Myanmar Prison A work of fiction by Alan Clements

Alan Clements: Daw Suu, as we near the culmination of our conversations, I am haunted by the transcendent grace of those nine nights I spent in communion with Sayadaw U Pandita in 2016, mere months before his passing. We’ve explored at length your own profound encounters with him, particularly on the Dhamma’s luminous qualities of leadership, the fierce, tender courage required to embody them in service to others. You reminded me that even when we stumble, the true calling is to rise anew and persist.

You spoke of authentic leadership as rooted in the qualities of a kalyāṇa mitta—a noble spiritual friend. If memory serves, these include: personal warmth and impeccable conduct (piya), unassailable integrity and reverence (garu), a presence worthy of love and veneration (bhāvaniya), speaking truth with unflinching clarity (vattā), the humility to embrace critique (vacanakkhama), and an unwavering refusal to exploit others for gain (no c’āṭṭhāne niyujjako).

Would you share further how these timeless teachings resonate within Myanmar’s revolutionary struggle for liberation—and with you, here, in the day-to-day of solitary confinement? These qualities seem indispensable, not only for today’s movement but for the promise of principled leadership, the world over, in the decades ahead.

Aung San Suu Kyi: Alan, Sayadaw U Pandita’s teachings radiate with timeless truth, their weight magnified amidst the fury that engulfs our nation. Leadership, in its deepest essence, must be anchored in ethical resolve and an unyielding duty—not only to oneself, but to the collective, and to generations yet to dawn. Without the spirit of kalyāṇa mittatā, leadership falters, brittle and hollow. And when leadership fractures, the spirit of the revolution shatters in its wake.

In my country, our quest for freedom demands more than courage. It requires a clarity of heart, a wisdom that pierces the veil of terror and chaos. A revolution without wisdom risks becoming a reflection of the very oppression it seeks to dismantle.

Our leaders, from the National Unity Government to the young visionaries forging paths in jungle enclaves, to the Ethnic Groups throughout the country—must resist not only tyranny, but the seduction of a hardened heart. They must embody integrity—unwavering, luminous, and alive in action.

They must cultivate forbearance (khamā), vigilance (jāgariya), relentless effort (utthāna), and generosity in sharing their strength (samvibhāga).

Above all, they must nurture compassion (karuṇā) and foresight (ikkhana)—virtues without which today’s sacrifices may become tomorrow’s sorrows.

These are not aspirational ideals. They are the bedrock of moral leadership, the scaffolding that sustains a revolution’s spirit. They are how we endure, not merely to survive, but to redeem.

Alan Clements: Sayadaw U Pandita also emphasized the necessity of foresight as a refined form of reasoning. He spoke of assessing whether an action is beneficial or harmful, suitable or unsuitable—and ensuring it brings no harm to oneself or others.

He reminded us that foresight must reach beyond the present; it is a form of care that extends across time. This echoes a Burmese proverb he once shared: “If you cannot help, at least do no harm.”

How do we cultivate such far-seeing compassion in the midst of relentless chaos?

Aung San Suu Kyi: It begins with mindfulness, Alan. Foresight is born of clarity, and clarity arises from sati—from intelligent presence. Without mindfulness, our actions are easily driven by reactivity—by greed, fear, or blind conditioning. But with mindful intelligence, we begin to see how our choices ripple outward across time, across generations. This is the antidote to the Wetiko spirit we’ve spoken of before—the devouring mind, insatiable, heedless of consequence.

To cultivate far-reaching compassion is to place ourselves in the hearts of the unborn. To imagine the world, they will inherit and to act with their welfare in mind.

The Buddha taught mettā, karuṇā, muditā, and upekkhā—loving-kindness, compassion, sympathetic joy, and equanimity, not as lofty ideals, but as the active intelligence of a conscious society. They are not passive. They are revolutionary. And they must become the compass of our political and spiritual lives.

Alan Clements: What still astonishes me, Daw Suu, is how satipaṭṭhāna reorders perception—not abstractly, but intimately. It dissolves that subtle veil between awareness and experience. Suddenly, sorrow isn’t just sorrow, it’s movement, sensation, impermanence.

And joy, too, is stripped of intoxication. Everything becomes workable. The Dhamma becomes immediate. Leadership, from that ground, feels less like control and more like attunement.

Aung San Suu Kyi: Yes, and that attunement is what protects us from cruelty disguised as necessity. Without satipaṭṭhāna, it’s easy to confuse reactivity for resolve, or silence for peace. The practice reminds us to pause; not out of hesitation, but out of integrity. Every mindful breath becomes a vote for nonviolence.

Alan Clements: And satipaṭṭhāna isn’t passive; it demands courage. To really observe the body, kāyānupassanā, or the mind in flux, cittānupassanā, is to see how often we reach for control, for permanence, for self. That shatters the spell of ideology.

I often wonder: how different would governance look if every leader were required to sit with their breath, their whole being, and examine their intentions before making decisions?

Aung San Suu Kyi: It would be revolutionary. Because satipaṭṭhāna doesn’t just sharpen awareness, it refines motivation. In politics, it is easy to cloak self-interest in the language of service. But mindfulness unmasks that disguise. It shows us whether our actions are born of lobha, dosa, or moha—greed, hatred, or delusion—or from something purer. Satipaṭṭhāna is accountability at the level of consciousness.

Alan Clements: Exactly. It’s where ethics and perception meet. And it’s why I believe the practice isn’t just therapeutic, it’s insurgent. It exposes the mind’s complicity in suffering. And if we’re brave enough to see that, we can lead without exploitation. We can resist without becoming what we oppose.

Aung San Suu Kyi: And in that way, satipaṭṭhāna becomes a form of service. Quiet. Steady. Inwardly luminous. It teaches us how to be free even while unfree. That, to me, is the true test of any leadership: how one behaves when stripped of status, stripped of praise. When there is only awareness, intention, and response. That is where character is forged.

Alan Clements: Daw Suu, we’ve spoken many times of King Asoka—the emperor who once bathed in conquest, only to awaken to the folly of violence and become one of history’s most luminous examples of ethical rule. His journey—from Chand-Asoka, the fierce and vengeful, to Dhamma-Asoka, the compassionate and wise—remains one of the rare moral inflection points in the annals of power.

It still astounds me: a sovereign capable of such cruelty choosing, in the aftermath of devastation, to renounce it. His remorse at Kalinga was not symbolic, it was seismic. A transformation of consciousness. His rule became a living covenant with the Dhamma: to lead not by fear, but by the power of conscience.

And now, as we speak, cruelty is once again unmasked across our world—in Gaza, where children’s bodies lie buried beneath rubble; in Ukraine and Russia, where an escalating war grinds entire cities into grief; and in countless zones of violence, repression, and trauma that barely register beyond the flicker of a headline. Myanmar, too, remains gripped by terror.

From this place in our shared history, where moral collapse and political violence have become global epidemics, how do we revive the legacy of Asoka? How do we bring his turning into the bloodstream of modern Myanmar, and perhaps into the conscience of the world? How do we midwife such a transformation in our time?

Aung San Suu Kyi: Alan, the story of King Asoka is not a relic. It is a mirror. And a question posed to every leader, in every era: when you come face-to-face with your own capacity to harm, to dominate, to deceive, to destroy—do you cling to it? Or do you change?

Asoka’s transformation was not merely political. It was psychological. Spiritual. He did not just halt a campaign of violence; he relinquished the worldview that had made it justifiable. He reimagined power as responsibility, not rule. And that is why his legacy endures, not because he triumphed, but because he awakened.

For Myanmar, this is not a historical lesson. It is a moral necessity.

Our revolution must undergo that same metamorphosis—not out of defeat, but through discernment.

Cetanā matters—intention shapes outcome. And so does samādhi—clarity that steadies the mind before it acts. If we are to rebuild our country from the ruins of atrocity, we must go beyond replacing tyranny with a new face. We must uproot its very logic. That means resisting not only bullets and propaganda, but also the subtle intoxication of vengeance.

Alan Clements: That distinction feels essential—not simply inverting tyranny, but transcending it. Because history shows us again and again: when the form changes but the mindset persists, the outcome remains the same.

Asoka’s transformation wasn’t the end of power; it was the purification of it. He governed not by threat, but by trust. His edicts carried not the weight of punishment, but the invitation to conscience. He institutionalized karuṇā and mettā. He used the machinery of state to support sīla, samādhi, and paññā—ethical conduct, steadiness of mind, and deep wisdom.

It makes me wonder: how many revolutions collapse not for lack of bravery, but for lack of inner reflection?

Aung San Suu Kyi: Yes, and that reflection must not be confined to books or monasteries. Wisdom is not abstract. It lives in action, in restraint, in the humility to feel the future in the choices we make today.

In Myanmar, cruelty surrounds us. But cruelty isn’t confined to the junta. It takes root wherever the heart forgets its own tenderness. And so, the deepest revolution—as we’ve often said—must begin within.

Asoka’s story reminds us that even the most brutal of histories can be interrupted by a single act of moral courage. That is why our movement must be guided not only by resistance, but by Dhamma. Not as decoration, but as design. Not as inspiration, but as infrastructure.

It must shape how we teach, how we heal, how we govern, how we forgive. As Sayadawgyi often said: Dhammo have rakkhati dhammacārī — “The Dhamma protects those who protect it.” That is not a slogan. It is a law of moral gravity.

If we build our nation on that foundation, then the freedom we birth will not just be a change in regime. It will be a change in consciousness.

Alan Clements: And that may be the most radical proposition of all: that liberation is not only the goal, but the method. The how determines the what. The seed shapes the fruit.

I think of the youth of Myanmar—risking their lives, forging new paths in the shadows of war. Many of them have never known peace. And yet, they are the authors of what comes next.

If Asoka’s turning lives on, it will be because they dared to make one of their own. Not in blood, but in paññā and mettā. Not through conquest, but through conscience.

May that be the turning history remembers; not as destiny, but as deliberate decision.

Aung San Suu Kyi: Yes, and I would speak to them directly—our youth, our revolutionaries. I know you are tired. I know you carry grief like a second skin. But please, do not let the fire that fuels your courage burn away your humanity.

There will be moments when rage feels more honest than hope; when the call for vengeance feels louder than the voice of conscience. That is precisely when mindfulness matters most. Not as retreat, but as refuge. As protection from becoming what we oppose.

If this revolution is to birth something truly new, then let it begin within—by refusing to let fear, hatred, or despair shape our next generation of leaders. True victory is not found in purity, or certainty, or punishment. It is found in the difficult, daily work of choosing clarity over confusion, compassion over cruelty, and presence over despair. That, to me, is the real Asokan turning—one the junta can neither see nor stop.

Alan Clements: Daw Suu, one of Sayadawgyi’s most intimate and powerful teachings was that we are related in four ways: as human beings, as world relatives, as beings bound by countless past lives, and as Dhamma companions. He said this understanding fosters compassion and mutual respect—that when we truly see one another through these lenses, we act differently.

He would often say, “It’s natural for people to help each other, and this should be done without self-interest. One shouldn’t want something in return. We should help with mettā and karuṇā.” In today’s world, where division has become doctrine and reactivity a reflex, how can this wisdom illuminate a new path—for Myanmar, and for the world?

Aung San Suu Kyi: Alan, Sayadawgyi’s teachings on interconnection are more than spiritual truths—they are a call to live differently. To see ourselves as world relatives is to dissolve the false boundaries of nation, race, creed, and ideology. When we act with mettā and karuṇā—with loving-kindness and compassion—we transcend self-interest and touch the essence of our shared being.

Myanmar’s struggle is not isolated. It echoes through every corner of the world where dignity is denied and truth is silenced. When we give without expecting return, we affirm the sacred bond of belonging. Sayadawgyi’s invocation—to give with the wish “May they be well; may they be happy”—reminds us that true generosity flows not from surplus, but from a heart softened by empathy. This is the tenderness that sustains revolutions and the quiet force that rebuilds nations.

To my fellow citizens, and to the world, I say this: Let us act not as strangers, but as kalyāṇa mittā—spiritual friends on the path. Bound not by blood, but by conscience. Let our actions be guided by love, by clarity, and by the joy of one another’s freedom. Only then can we co-create a world where peace is not an abstraction, but a lived reality.

Alan Clements: Daw Suu, as we close this chapter, what final message would you offer—to the people of Myanmar, to the revolutionaries, and to a world that still watches from the shadows?

Aung San Suu Kyi: To the people of Myanmar: Hold fast to the Dhamma. Let it guide not only your resistance, but your relationships, your values, and your everyday choices. This revolution is not only about the fall of tyranny—it is about the rise of a conscience-based society. A nation where every life is honored and every voice heard.

To the revolutionaries: remember, the highest victory is self-mastery. Resist not only the junta, but also the pull of lobha, dosa, and moha—greed, hatred, and delusion. Let your courage be anchored in compassion. Let your strength be forged in humility. Lead with wisdom, not wrath.

And to the world: stand with us—not only in sentiment, but in solidarity. The fight for Myanmar’s freedom is a thread in the tapestry of global justice. May we all cultivate the wisdom to see clearly, the compassion to act bravely, and the responsibility to shape a world where future generations may live, love, and flourish in peace.

Alan Clements: Thank you, Daw Suu, for your luminous vision and unwavering devotion to truth. May your words not only awaken the conscience of Myanmar, but stir the soul of our shared humanity—guiding us through these perilous times with the clarity of the Dhamma.

Aung San Suu Kyi: Thank you, Alan. May we all walk the path of Dhamma—with courage, with compassion, and with the faith to believe in a better world.

Alan Clements: And so, we conclude this extraordinary exchange—this sacred dialogue carried across silence and steel, from your solitude in captivity. I thank you from the depths of my heart: for all that you are, all that you have endured, and all that you continue to embody—not only for Myanmar, but for the conscience of the world.

Your life, your moral clarity, and your unshakable devotion to justice light a path of dignity for us all. May the radiance of your spirit—and the fearless heart of Myanmar’s revolution—guide the birth of a future worthy of our noblest humanity: a future free from tyranny, from hatred, and from the blindness of indifference.

And may all those entrusted with power—now and in times to come—awaken to the sacred strength of redemption. Not as spectacle, but as sincerity. Not as weakness, but as the ultimate expression of humanity.

If there is one light I carry forward from this dialogue, Daw Suu, it is this: the revolutionary power of consciousness, of conscience, and of the courage to reclaim what is just and true.

Let this be our call: to reach into the deepest recesses of our being, to resurrect the virtues of dāna, sīla, and bhāvanā—generosity, ethical integrity, and inner cultivation—and from these roots, correct our wrongs, elevate our character, and embody the promise of peaceful coexistence.

From my heart to yours, Daw Suu: live on, luminous voice of truth. Live on, steadfast guardian of freedom. May your words ripple through the marrow of history and awaken every soul to its noblest potential.

Thank you. Thank you. Thank you.

Aung San Suu Kyi: Alan, thank you—for your friendship, your courage, and for being a revolutionary witness to our story. In the darkest times, it is the Dhamma that lights the way. Let it be our compass—guiding us through fear, through grief, and toward a future stitched with unity and compassion.

May we never forget our shared humanity. May we choose love over fear, wisdom over division, and action over despair. And may we live not just for ourselves but for one another.

Together, we can rise—rooted in peace, anchored in justice, and nourished by freedom.

From my heart to yours, Alan—and to all who walk this path of hope: thank you. Sādhu.

THE TRILOGY All proceeds to the non-profit Use Your Freedom Campaign

For further details, cinematic video trailers, and access to all online booksellers worldwide, visit

Conversation with a Dictator: A Challenge to the Authoritarian Assault — A fictional dialogue confronting the psychology and moral architecture of dictatorship.

Details & online sellers: https://www.worlddharma.com/items/conversation-with-a-dictator/ (worlddharma.com)

Unsilenced: Aung San Suu Kyi — Conversations from a Myanmar Prison — A witness dialogue rooted in Dhamma, conscience, and the lived reality of nonviolent resistance.

Details & online sellers: https://www.worlddharma.com/items/unsilenced-conversations-with-aung-san-suu-kyi-from-a-myanmar-prison/ (worlddharma.com)

Politics of the Heart: Nonviolence in an Age of Atrocity — A global call to conscience—exploring nonviolence as moral intelligence, civic duty, and spiritual resistance.

Details & online sellers: https://www.worlddharma.com/items/politics-of-the-heart-nonviolence-in-an-age-of-atrocity-psychedelic-activism-and-the-end-of-war/ (worlddharma.com)

Use Your Freedom —

https://www.useyourfreedom.org

. (facebook.com)

Wishful fictional thinking does make reality happen. The rounds of rebirth become happier when we practice Dhamma, but it won't fix the world. Especially not the world of politics and humans. It could but it won't. Even the Buddha did not say he could fix the world, he did however teach us how to escape from the rounds of rebirth. So creating a fictional narrative and putting your words into the mouths of others as if they agreed with you is quite offensive to those individuals legacy. It is better to let them speak for themselves. Unfortunately there are always people going from light to light, light to dark, dark to light and dark to dark. That is nature. The darker a mind the harder it is to see light. Min Aung Hlaing does not have the wisdom to escape from his darkness. He is no Ashoka who didn't take long to realise his mistake. Ashoka was not killing his own people. He was much smarter than that.

Profoundly moving portrayal of moral leadership under duress. The Asokan transformation you frame here—from conquerer to conscience—cuts to the heart of what revolutionary change actually requires beyond structural shifts. When Daw Suu distinguishes between inverting tyranny versus transcending its logic, that captures somethng I've rarely seen articulated so cleanly in political discourse. The satipaṭṭhāna as insurgent praxis idea is particuarly sharp.